18 Sep 2015

Five reasons to try API-first development

by Joe ClarkI confess that I’m a data geek. When I first discovered relational databases in this tutorial by Jay Greenspan over 15 years ago, I began to see the world in third normal form. When I learned about RESTful web services from Michael Mahemoff’s Ajax Design Patterns, I started to think about applications in terms of requests and responses. I love discovering well-crafted JSON web services and showing them to my students, and so the idea of creating a public API to let other people obtain data from one of my databases or applications is not at all alien to me.

But it never occurred to me to build the API first.

I got the idea while developing a data engineering class. I wanted to emphasize the point to my students that analytics is about building data products for others to use and that, before we got into the nitty-gritty of how to use various types of databases, they should be able to think about what sort of operations on data their users needed to make, what sort of data inputs and outputs the systems ought to have. As a hands-on lab, I had them develop mock APIs using Python and Flask. Essentially, they were using a web development framework but serving up JSON instead of web pages. Offhand, I told them that if they were working with front-end developers, the latter could go ahead and build web or mobile apps to read and write data via the API—even though the APIs were entirely fake at this point, just serving up sample data. (We’ll connect them to real databases in a couple of weeks.)

Then I realized—I’m an app developer, and this would work for me, too!

API-first development

The core idea of API-first development is that rather than building an API for others to access your data, as an afterthought to building a system, you build your application from the beginning as an API that describes all of your application’s operations on data. Then you begin to build the front-end while implementing real back-end functions in place of an initial mock-up . Turns out I’m not the first to think of this, see here and here, for example.

Specifically, if we’re talking about a RESTful web service API, this means setting up a bunch of URL endpoints and HTTP methods, one for each use case. Mock these up by putting fake data at each URL endpoint. Code like this, for example, would serve to fake an API endpoint in Python’s Flask framework and could be deployed right to Heroku:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

import os

from flask import Flask, jsonify

app = Flask(__name__)

# listing all items

@app.route("/api/items", methods=['GET'])

def list_items():

fake_data = { "items": [ {"name":"Widget","id":42,"price":49.95},

{"name":"Doodad","id":43,"price":19.95},

{"name":"Gizmo","id":44,"price":99.95} ]

}

return( jsonify(fake_data) )

if __name__ == "__main__":

port = int(os.environ.get("PORT", 5000))

app.run(host='0.0.0.0', port=port)

Once you had this running, you could then split into two groups. The front-end developer(s) working on the web (mobile) applications could build their pages (screens) to display the data they consume from the API. They shouldn’t care that the data is fake, as long as there’s enough of it to effectively test their designs. The back-end developer(s) could then take the API one endpoint at a time and replace the temporary code with real business logic that queries the real database.

Five reasons

I have begun to encourage the students in my information systems capstone class, who are all engaged in developing mobile and web apps, to adopt API-first development, and I am trying it out in my own startup as well. Here are five benefits I expect to get from it:

#1: It focuses you on use cases and data processing

Notice the inversion of the usual way we develop data-driven apps. Since I started designing web sites in 1995, it has always been about the front-end first. We think of our architecture in terms of “pages” or “screens”. Data and logic are added on later with PHP, Javascript, or other types of code inserted somewhere, literally subordinate to the <HTML> tag of a page. As a result, we cannot implement or test the business logic until the pages are mostly complete. Moreover, it distorts our thinking. Pages and screens don’t correspond exactly to use cases or to data entities, so front-end-first design may prevent us from figuring out what our true requirements are until well into a project.

If we design the API first, however, we are forced to think of our application instead as a system that performs operations on data. We have to consider the entities and relationships in our data model, enumerate the use cases, and document the inputs and outputs to each type of operation. Developers should get a clear picture of how many pieces of code they will need to implement, and they get it at an early stage.

#2 It becomes effortless documentation

When you design the API first, the plan of implementation itself describes URL endpoints, HTTP methods, and specific data structures for inputs and outputs, which can later be recycled as an instruction manual or reference for future development. Much like Tom Preston-Warner’s README-driven development, “you’re giving yourself a chance to think through the project without the overhead of having to change code every time you change your mind about how something should be organized”.

Drafting the API documentation right out of the gate gives you an artifact that other developers can comment on and coordinate their own work with. Front-end developers get sample JSON code to work with, and database developers know what they’re trying to implement. Writing the instruction manual first also helps to prevent “feature creep” in which developers add “nice to have” functionality to a product that didn’t really need to be there.

#3 It guides database modeling

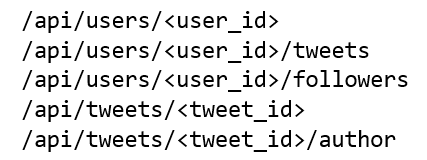

A well-designed API is expressed as a set of URL endpoints that locate “resources” in the application’s domain. If they follow good REST principles, these URLs happen to look a lot like a folder structure. For example, a few endpoints for a Twitter-like application might include:

API endpoints for a Twitter-like app

API endpoints for a Twitter-like app

When you think about it, you realize that this “folder structure” could never exist on a real disk: it has tweets stored under the users, and users stored under their tweets. Even more oddly, users seem to be stored under the other users that they’re following. That’s not hard to implement, though, because modern web frameworks allow us to easily define these kinds of URL structures that don’t correspond to the actual locations of data on disk.

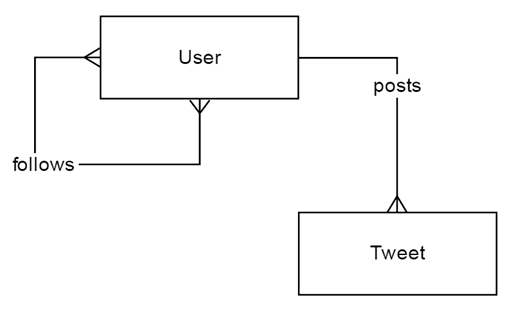

What’s happening here is actually a sort of entity-relationship modeling! The simulated URL structure shows that each user can publish multiple tweets, but that each tweet has only one author—a good old-fashioned one-to-many relationship. And each user can be a follower of other users, and followed by any number of users: many-to-many.

ER model implied by sample API endpoints

ER model implied by sample API endpoints

The exercise of dreaming up URL endpoints for all resources in the application can serve as valuable precursor to database design, as these can be intuitively translated into an implied entity-relationship diagram. In particular, I think it would be a very valuable exercise for those using NoSQL back ends, since NoSQL doesn’t otherwise force developers to think this way about their data models.

#4 It allows you to pivot.

One of the key reasons I’m using API-first development in my startup is the Lean Startup notion of the “pivot”. We’ve got several hypotheses about our value proposition, and I anticipate evolving the product to try out several of them. We might even run several versions at once under different domain names and front-end designs. But I don’t want to re-write all of the SQL and business logic each time, especially not for very similar sites.

By developing the API for the back-end first, I can plug and play different kinds of front ends, even running them at the same time. Multiple businesses could in fact be built on the same set of data services I’m developing, and it’s not inconceivable that we could sell one of them and keep developing others, or rent out the back end to other startups.

My students, too, often switch technology in the middle of CIS 440. It’s a very common phenomenon that they set out to make a native mobile app and end up settling on a mobile-responsive web application instead, or set out to learn a new language (e.g. Java) and do their project with it, only to find it too challenging and switch later to a tool they know, such as PHP. With an API designed first, they could switch out either the back-end, the front-end, or both, without derailing their projects.

#5 It’s more compatible with Agile

Agile approaches vary, but they all have one thing in common: strict prioritization of requirements. Feature A needs to be done before Feature B and Feature B needs to be done before Feature C. But, what if the homepage needs twenty different buttons or other controls? It’s not always easy to figure out which one to do first. Without the distraction of a front-end, developers and product owners will be working with a list of CRUD operations on data entities (resources). These must by necessity be atomic, and if listed in any kind of order, they amount to a strict prioritization of the API development backlog. Developers can begin coding them without having to adjust them due to later front-end changes, and they have no excuse to stand around waiting in between releases of the front end.

Researchers have shown that when businesses operate in chaotic environments, they succeed by embracing constrained flexibility, that is, allowing experimentation and adaptation but controlling it with simple rules. (cf. Brown & Eisenhardt, 1997). Light structure outperforms heavy structure, and also outperforms unstructured, ad hoc decision making. API-first design is a model for applying light structure to application development: the API functions as a “contract” between developers on the team, and their eventual users, but allows infinite flexibility in how to deliver on what is agreed.