21 Oct 2015

Design is a science

by Joe ClarkPhilosophy of the artificial

For many centuries, there has been a distinction made between natural science on the one hand and engineering or applied science on the other. The natural sciences, physics, chemistry, biology, etc., are branches of philosophy—the pursuit of truth. Along with the humanities, the natural sciences were recognized as important parts of a liberal education and enjoyed great respectability among academics. More recently, the social sciences such as psychology and sociology have taken their place in academia.

By contrast, the various applied and professional disciplines have been seen as non-philosophical, concerned with usefulness rather than truth. Although engineering, medicine, business, law, education, architecture and similar problem-solving disciplines did convey useful bodies of knowledge, it was hard to see any “theory” in them. After all, techniques and technology were constantly changing. They emphasized prescription of solutions rather than description of the world as it is. As a result, many faculties in the professional schools preferred to focus on fundamental science and not on the domain knowledge their graduates would need at work. Business schools taught economics but not business planning, engineering schools taught physics but not design, and so on.

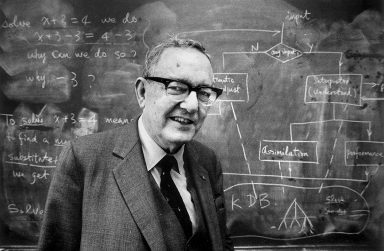

Universities were faced with an unhappy choice: teach what was useful today without the philosophical rigor that would enable graduates to adapt their knowledge or abstract it to other domains, or teach the fundamental sciences and leave its graduates unprepared to apply their knowledge in real-world problem solving. The way out of this dilemma was charted by one of the past century’s great geniuses, Herbert A. Simon.

In The Sciences of the Artificial, Simon laid the foundations for a philosophy of the artificial and a science of design. Artificial (i.e. “man-made”) things surround us. They are constrained by physical laws and, if we want, we can study them “objectively” using the natural sciences: for example, a physicist could take an airplane as a given and study the way it is affected by the flow of wind. But this doesn’t really capture the whole truth of the artifact. An artifact such as an airplane also embodies certain goals that we need to grasp if we are to understand it.

“If science is to encompass these objects and phenomena in which human purpose as well as natural law are embodied, it must have means for relating these two disparate components.” (Simon, p. 3)

An artifact for Simon could be seen as a meeting point between an “inner environment”, the way the artifact itself worked, and an “outer environment”, the problem it addresses and the context in which it operates. The relationship between the inner and outer environments is where we find human purpose. A problem solver, engineer, or designer is someone who tries to make the inner environment appropriate to the outer environment. For example: for the inventor of an airplane, the outer environment is characterized by the known laws of gravity and air pressure. He makes choices about the inner environment (the materials to use, the type of engine, and so forth) in order to achieve a goal—flight.

The philosophy of science of design

In order for a science of man-made things to be intellectually rigorous, philosophically weighty, abstract, and teachable, therefore, it would take the form of a science of design. Unlike a trade school education, which teaches about existing artifacts (technologies, processes, methods), a science of design seeks theories about how to develop artifacts. It may be a science of design processes rather than of the things that result from design.

Simon suggested a number of elements or features that theories of design might incorporate. First, these theories would have to address the question of how designs would be evaluated. The naive assumption that is conveyed by economic theory (not a design science) is that problem-solvers seek the “optimal” solution to every problem. For most complex problems, though, it is impossible to find the optimum or to know if you have found it. Instead, criteria for evaluating designs are usually phrased in terms of minimum requirements. Designers satisfice, that is, they work until they find “good enough” solutions. Unlike a math problem, a design problem usually doesn’t have one uniquely correct solution.

Design theories must also address the question of search, since most design solutions cannot simply be optimized or solved mathematically, nor can they be deduced intuitively. With problems of any significant complexity, solutions also cannot simply be designed by adding up known cause-effect relationships. An architect may know the properties of various materials and structures, and a medical researcher may know the isolated effects of various treatments, but when assembled together they may have interactions or side effects that could not be foreseen. Thus, for complex problems designers must follow some process of developing solution alternatives (simulated or actual) and evaluating them as wholes.

It may be the case that different methods of logical reasoning are employed in design, although it is not necessary. In the natural and social sciences, which strive for description of the world as it is, one observes a cycle of induction and deduction. Inductive reasoning observes natural or social phenomena and derives theories to explain them, with the hopes that these theories can be generalized to apply elsewhere. Deductive reasoning derives hypotheses from these theories, which can then be tested to confirm or disprove the generalizability of the explanations. By contrast, a design theorist seeks prescriptive or normative knowledge and in design we often see an abductive mode of reasoning. In abductive reasoning, a designer considers a variety of competing hypotheses at the same time, and through iterative designing filters some of them out and settles on one or a few that seem to have held up best in his experience with the real world.

There has been substantial thinking in many domains about the best ways to embark on the search for designs. In CIS 440, students will learn about a variety of approaches to developing information technology and information systems. Because there may be more than one satisfactory solution to any given problem, the design process may have a great effect on which solution, or which style of solution, is ultimately arrived at. Even if different design approaches all achieve satisfactory solutions according to the same evaluation criteria, the solutions they achieve may be radically different.

Design science in information systems

I argue that my field, information systems, is a science of the artificial and ought not to be counted (as it typically is) among the social sciences. Although much of the research in our field takes information systems artifacts as “given” and tries to theorize social phenomena like technology choices, as if the researcher was aloof to the goals of his subjects, this research is properly seen in support of a larger mission: to generate prescriptions that really help practitioners. To do this, we draw on descriptive knowledge of how the world is but strive for what should be.

“Everyone designs who devises courses of action aimed at changing existing situations into preferred ones.” (Simon, p. 111)

Scholars within our field have written a great deal about design research in the past several years (e.g. Hevner et al, 2004). Alan Hevner has been the most outspoken proponent of the idea that design is an inalienable dimension of a full understanding of information systems.

“While natural science research methods are appropriate for the study of existing and emergent phenomena, they are inadequate for the study of ‘wicked problems’ which require innovative solutions. Such problems are more effectively addressed using design research methods.” (Hevner, 2009).

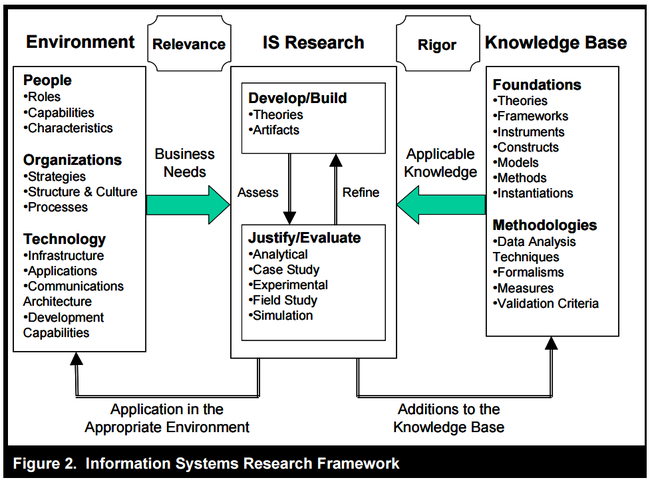

Figure 2 from the 2004 research paper by Hevner and colleagues shows that IS research must prove its relevance by addressing business needs, and prove its intellectual rigor by contributing generalizable knowledge to a scientific knowledge base of theories, frameworks, and models.

This sets a standard for design research to obtain academic respectability. Merely “designing” is not design science research if it does not solve a new problem or uncover new general knowledge, connecting it to the extant knowledge base.

“Rigor in design research is what separates a research project from the practice of routine design.” (Hevner, 2009).

The outputs of design research are not just new artifacts but new types of artifacts, or new principles, methods, or models for creating them. To contribute to the knowledge base of our discipline, researchers document their findings as information systems design theory (e.g. Walls et al, 1992; Gregor, 2006). One way of documenting a design theory is outlined by Jones and Gregor (2009):

- Purpose and scope (what the system is for)

- Constructs (the causa materialis)

- Principles of form and function (the “blueprint”)

- Artifact mutability (the changes or adaptations possible)

- Testable propositions (which could be tested to prove/disprove the theory)

- Justificatory knowledge (background data or theory underpinning the design)

- Principles of implementation (how to build it)

- Expository instantiation (case study or prototype to demonstrate it)

What I think is important for students to note is that, if you can understand your own designs in these kinds of terms, you begin approach problem solving in information systems not only as a tradesman but also as a philosopher. You can see how a particular type of solution can be applicable to other problems, and identify the limits of any design principles or heuristics you’ve developed. Moreover, if we as faculty are only teaching you what to do but not why it works, we aren’t adequately training you as thinkers.

Practical design thinking in information systems

The next question to answer is: what theories do we already have, in 2015, to guide information systems designers and problem solvers? There are several which you may find presented in textbooks as methods or processes for project management, product development, and engineering. Indeed, the practice of information systems development (ISD) has gone through several phases and is still in continuous flux. Traditional project management methods (PMBOK-based) have given way to a variety of Agile models, and these themselves are now being supplanted by new concepts: design thinking, DevOps, and the Lean Startup. In CIS 440, I will explore with my students a sampling of the best current thinking about how to develop IT products. A few common threads unite all of these methodologies:

-

Pay attention to process.

In classical economics, to be “rational” is to make the optimal choice. This is a substantive rationality—the choice itself is deemed to be rational if it is the best possible choice. Herbert Simon and his students developed a concept of procedural rationality in which we evaluate the process of search rather than the ultimate choice. This is important in the real world of problem solving and design where there may be no optimal solution, or if there is we are unlikely to find it. A rational process for decision making might include developing criteria, identifying alternatives, and evaluating alternatives until a satisfactory one is found. Importantly, one satisficing decision maker may make a different choice than another even given the same set of alternatives, and this does not imply that they are irrational.

In CIS 440, I will not attempt to lecture students on what is the “best” IT architecture or the “optimal” design for a piece of software. Instead, we will focus on best practices in the development process. Importantly, many of these practices have built-in mechanisms for reflection and continuous improvement on the process itself. Scrum, for example, has regular “review” meetings that evaluate the artifact being developed, as well as “retrospective” meetings to evaluate the team’s own processes.

-

No facts in the building.

The direction of evolution of ISD processes has been away from “big design up front” (BDUF) methods where all planning was done by the project team and project manager, toward increased contact with the business and the ultimate customers. The Agile movement made the client explicitly a part of the development team, in the Product Owner role. Instead of getting requirements from a document, they would be elicited by regular back-and-forth with this representative of the business’s interests.

Newer approaches to IT product development, such as the Lean Startup, take advantage of analytics to go one step farther: instead of asking the client to interpret what the business needs, teams are to go directly to the end users (i.e. the client’s customers who will use the technology). And instead of asking them what they want, developers increasingly use hard data about what they do with the product. As Stanford’s Steve Blank tells his students:

“There are no facts inside the building so get the heck outside.”

We will examine the different approaches to, and technologies for, eliciting feedback from clients and end users during design.

-

Iteration.

Modern IS development approaches are iterative. Traditional project management methods like those used in construction and aerospace turn out not to work very well in IT, because IT projects are more complex (as opposed to complicated) and planning up front is difficult. Therefore, most of the newer methods replace up-front planning with continuous re-planning or “just-in-time planning” of small chunks of a project. But how do you plan only a small part of a system, when other parts of the system will depend on it? And moreover, how do you explain an incomplete plan to a client, or get them to sign a contract on it? These are some of the challenges that new ISD approaches need to meet.

-

Commitment to experimentation.

Complex problems cannot be solved in a planning meeting; instead, it requires lots of trial-and-error. Increasingly, ISD methodologies are moving toward a scientific mindset, a necessary development because a major part of trial-and-error is error. Designers and their managers must see designs as hypotheses and take a scientific attitude toward failure—as in science, an experiment that disproves a hypothesis teaches us as much, or maybe more, than one that supports a hypothesis. An oft-repeated mantra (usually attributed to Tom Kelley of IDEO is

“Fail faster to succeed sooner”

We will study how to use designs as hypotheses and to use empirical data to learn from them. In addition, we’ll see the importance of certain engineering or DevOps practices like continuous deployment in enabling organizations to speed up their engines of learning, and how this can changes organizational culture, strategy, and the bottom line of innovation.

Conclusion

I have argued that there is a philosophy of designing—an important perspective on our field as a science of the artificial, which students should be exposed to in order to adequately prepare them for thinking intellectually about information systems. In addition, there are a number of methodologies or theories of how to design information systems products and solutions. Because these are parts of the theory of IS design, they are formalizable and teachable. Moreover these methods themselves have aspects of the “scientific method” in that increasingly they involve explicit articulation of design hypotheses, iterative experimentation, and use of empirical data. In teaching my students to be IS designers, I hope to also teach them to be design scientists.