04 Nov 2015

Is science design? Prototyping in academic research.

by Joe ClarkI have argued that design is a science, with particular reference to information systems development. There is a philosophy and a body of theory on how to design software, data, and socio-technical information systems in organizations. But what if the output we are working toward is scientific knowledge? I believe, but have not yet proven, that we can treat science itself as a design activity. In the spring of 2016, my capstone class will take part in an experiment to figure out just what this might mean.

What kind of problem is science?

Horst Rittel and Melvin Webber of U C Berkeley articulated the concept of “wicked problems” in a noteworthy 1973 paper. Their purpose in using this term was to argue that problems like public policy cannot be solved by simply hiring experts to apply professional knowledge (“science”). Problems of social policy were different, they argued, because these problems cannot be definitively described (or “tamed”). Wicked problems defy definition, because there is no agreement among stakeholders about the goals, there is no unequivocal measurement of outcomes, no way to know when the problem is “solved”, and no hard boundaries around the system where a problem seems to be found.

They identified ten features of wicked problems (Rittel & Webber, 1973):

- There is no definitive formulation of a wicked problem.

- Wicked problems have no stopping rule.

- Solutions to wicked problems are not true-or-false, but good-or-bad.

- There is no immediate or ultimate test of a solution to a wicked problem.

- Every solution to a wicked problem is a “one-shot operation”; because there is no opportunity to learn by trial-and-error, every attempt counts significantly.

- Wicked problems do not have an enumerable (or an exhaustively describable) set of potential solutions, nor is there a well-described set of permissible operations that may be incorporated into the plan.

- Every wicked problem is essentially unique.

- Every wicked problem can be considered to be a symptom of another problem.

- The existence of a discrepancy representing a wicked problem can be explained in numerous ways. The choice of explanation determines the nature of the problem’s resolution.

- The planner has no right to be wrong.

Farrell and Hooker (2013) simplify these ten criteria to three cognitive features of a problem situation that together determine its “wickedness”: the finitude of our cognitive capacities and resources, complexity or entangledness of consequences, and normativity constraints—the value conflicts among stakeholders.

“Each of these features poses a challenging aspect of the fundamental methodological problem: how is it possible to act intelligently and responsibly in a world characterized by deep limits on our problem-solving capacities? We contend that it is the depth and extent of this methodological challenge that ultimately constitutes the wickedness of a problem.” (Farrell & Hooker, 2013).

Are scientific research challenges “tame” problems, that is, are they well-defined, bounded, and do they have clear success criteria? Another way of asking the question is: does there exist a body of professional or expert knowledge about how to get from point A to point B in science?

Tame problems are those to which professional knowledge, engineering discipline, or well-honed art, can be applied in a straightforward manner. The professional’s experience, skill, time, and resources are the primary determinants of success, or so the thinking goes. Wicked problems are the domain of designing; solutions must be found, not simply identified and applied. Design is distinguished in this way from science:

“[D]esign problems are ill-defined, ill-structured, or ‘wicked’. They are not the same as the ‘puzzles’ that scientists, mathematicians, and other scholars set themselves” (Cross, 1982).

Perhaps these authors are beating something of a straw man of “science” in order to advocate for more interest in theory of design; because at first glance it seems to me that scientific research matches many of the characteristics of wicked problems, except #5 and #10, because trial-and-error are certainly possible in science. (Those exceptions also should apply to other species of design problems from architecture to zydeco.) Criteria #4 and #8 resonate with the cliché about science, that every answer raises another question. Furthermore, criterion #9 reminds me of something Weick wrote about theorizing:

…it was argued that a reaction such as ‘that’s interesting’ was sufficient to selectively retain a conjecture, independent of additional efforts to verify it. Eventual attempts at verification may occur sometime later but… the value of a theory does not ride on the outcome of those tests. The reason it does not is that validation is not the key task of social science. It might be if we could do it, but we can’t—and neither can economists…

If validation is not a criterion for retaining conjectures, this means at least two things. First, the criteria used in place of validation must be explored carefully since the theorist, not the environment, now controls the survival of conjectures. Second, the contribution of social science does not lie in validated knowledge, but rather in the suggestion of relationships and connections that had previously not been suspected, relationships that change actions and perspectives. (Weick, 1989)

In other words, at least in the social sciences, we can never really rule out a theory (or a design?) in the way that a physicist or chemist could disprove a hypothesis, as long as there is one researcher who still believes in it.

Re-reading Weick’s (1989) “Theory Construction as Disciplined Imagination” just now, another excerpt jumps out at me:

Natural scientists pick problems they can solve, work for colleague approbation rather than lay approbation, collaborate with people who share their interests and values, and seldom worry about what others think. The world of the social scientist, poet, theologian, and engineer is dramatically different. These people choose problems because they urgently need solution, whether they have the tools to solve them or not.

So maybe the answer to my question is “it depends”. Some scientific problems are tame, merely requiring the patient application of skill and elbow grease, while others are wicked and remain problems as long as anyone cares to grapple with them. Perhaps science becomes more like design in areas where there are multiple potential theoretical explanations and not enough knowledge or resources to explore them all.

“This commonality [between design and science] becomes still clearer whenever scientists venture into new unexplored territories, e.g. from Newtonian into relativistic or quantum domains, or where scientists are fundamentally re-evaluating previously explored territory… in short whenever scientists are engaged in deep or revolutionary research.” (Farrell & Hooker, 2013)

How does design apply to wicked problems?

If a scientific problem is wicked, the literature agrees that design thinking is the way to approach it. I’d like to review for a moment how the literature describes design thinking, beginning with Farrell and Hooker, who describe three cognitive stages at work in solving wicked problems:

“(I) an initial phase of problem space formation where the context of the design situation (e.g. location, interested parties), the general possibilities of the design situation, the putatively desired outcome of the design process and the normative constraints applicable to it are each initially characterised, followed by (II) a development/exploration phase where a trial space of various potential partial solutions (e.g. in sketch or model form) is developed and explored and are allowed to mutually interact and are modified, often in interaction with negotiated modification of any and all of the elements of the initial phase (the problem re-definition aspect) so as to access new resolution pathways and realisation of value, and (III) a final production phase where the design outcome is produced and normative value realised.” (emphases mine)

Similarly, Herbert Simon (mentioned in my previous post) describes design as a search process which can be characterized as a cycle of generating and testing alternatives. We can

“think of the design process as involving, first, the generation of alternatives and, then, the testing of these alternatives against a whole array of requirements and constraints… The generators implicitly define the decomposition of the design problem, and the tests guarantee that important indirect consequences will be noticed and weighed” (Simon, 1996, pp. 128-129).

IDEO, the leading firm in the “design thinking” revolution, also describes their process as having three parts: “inspiration”, “ideation”, and “implementation”:

“Inspiration is the problem or opportunity that motivates the search for solutions. Ideation is the process of generating, developing, and testing ideas. Implementation is the path that leads from the project stage into people’s lives.” (Source: IDEO)

The middle phase, ideation, is where we see a real break from the world of “tame problems”. Designers strive to generate and test out as many ideas as possible before running out of time and money. Collaborative brainstorming, rapid prototyping, and an abundance of feedback are the hallmarks of design thinking, and they replace the professional approach of hiring an expert to apply known techniques. “Enlightened trial and error succeeds over the planning of the lone genius.”

How do scientists design?

I think it is pretty straightforward to imagine how “problem space formation” occurs in science; whether driven by a new observation or from a scientific answer that generates a new question, scientists are inspired to work on something new. In addition to identifying the problem, they come up with multiple possible avenues for solving it, and a new formulation of the research question that corresponds with each.

The final production phase for science-as-design is constrained by standard means of documenting and publishing research: the objective is a conference presentation, a journal article, a book or maybe a patent. So we know that at some point there must be a stopping point for search, a decision made to publish results.

But what does the middle phase look like? Given a number of possible problem formulations, in science

“…just as with design, the issue becomes which few of these possibilities is currently most worth pursuing and in which specific forms. Various options will be developed in more detail, their resource demands and risks analysed and their merits spelled out for consideration. During that process more specific versions of the initial general problem will be developed, some of them … perhaps requiring a significant reformulation of both what the problem is and what criteria a solution would need to meet. A critical debate will develop about these options, the upshot being that one or two of them will be selected to pursue, perhaps by individual laboratories, perhaps as cooperative ventures. After the results of that round are in, the whole process can be repeated again and again until an at-least-satisfactory explanation emerges within the investigatory resources available.” (Farrell & Hooker, 2013)

This is, of course, making the point that a scientific field “designs” at the field level—each researcher or institution is playing a small part in a large search process. My intent, however, is to show how a single research paper by a student (not a whole program of research) can be seen as a design activity. What would design of an individual paper look like? What could be prototyped and done iteratively in a “one shot” study?

Cross (1982) made an interesting observation that designers take a solution-focused approach to problem solving while scientists take a problem-focused approach. Scientists analyze and try to discover the “rules” that would determine an optimal solution, whereas designers are more likely to begin proposing solutions and ruling them out. Though this sounds atheoretical, designers did tend to learn quite a bit about the “rules” as a result of their solution-focused result: “In other words, they learn about the nature of the problem largely as a result of trying out solutions, whereas the scientists set out specifically to study the problem” (Lawson, 1980, quoted by Cross, 1982).

Building on that thought: if the goal I want to give my students is to discover theory (or at least generalizable knowledge of some kind, learning that can be transferred from a sample or case study into other situations), perhaps I should guide them in a solution-based approach and trust that, by some process of empirical and abductive reasoning, they will arrive at a theoretical understanding of the problem. These “solutions” might take the form of technology prototypes to be subjected to a process of elimination. There should be some process of reflection on each prototype, a reflection which generates new hypotheses. This should be an iterative process and some synthesis of hypotheses should be the final step after time runs out.

Having written that down, it doesn’t sound too different from the normal process of research—generate multiple hypotheses, eliminate some of them by an experiment, and reflect on what the findings mean. Perhaps the difference is in the order in which these activities are undertaken.

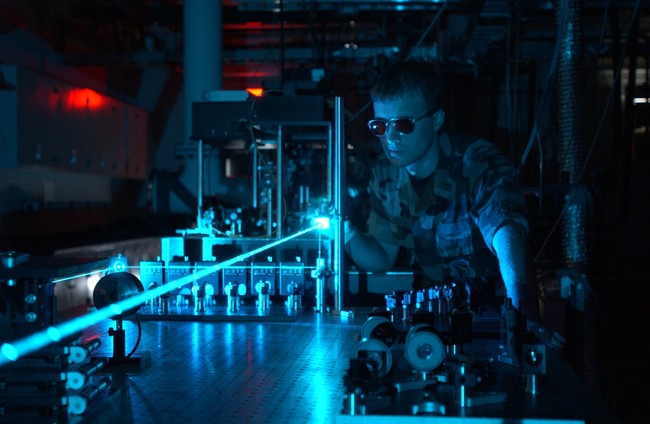

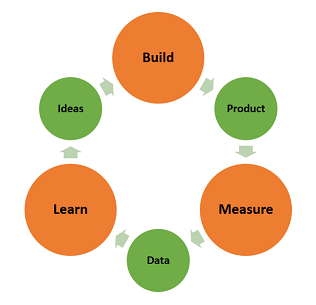

Eric Ries proposes a “build-measure-learn” loop for entrepreneurs, which suggests that they build prototypes in order to gather data in order to evaluate one business hypothesis at a time. I find that this loop tells us something about scientific search if we read it backwards, that is:

- First we decide what we want to learn (i.e. a theory we want to bet on).

- Then we decide what data would be needed to prove or disprove it.

- Finally we design the cheapest or quickest possible experiment that could give us such data.

What if as a scientist, instead of planning the study first, we started by deciding on the theoretical contributions that we think we can make. Then identify the bare minimum data needed to eliminate our ideas—for example, could one phone call with a practitioner rule out an idea before money and time are spent on other data collection? Then iterate, until we find an idea that we genuinely need a significant effort to learn about, and do that as our study. I don’t know if I’ve really hit upon something new here, but it gives me a new way to think about how to do research.

Designing research in CIS 440

Given certain constraints in the course—for example that it must be graded in three milestones (initial proposal, literature review and analysis, final term paper)—I am not focusing at this time on redefining the project. At the end of the semester, students will need to produce something like a traditional research paper with theory development and the results of an empirical study. My thoughts therefore are on what I can do within the class time that would enable them to approach their research as designers.

The following are some ideas I’m developing for the spring semester:

-

Problem discovery: Students have three weeks to come up with their project proposals, but I don’t want them chewing on their pencils the whole time. Instead, I plan to force them to brainstorm ideas in a group workshop. After talking about the genres of information systems theories, I propose to prompt them with everything from xkcd and Dilbert cartoons to magazine articles and tweets and challenge them to describe theories that they imply. Then, in the next class, I’ll ask them to rapidly generate as many problems-for-research as they can. There’ll be an activity to rapidly categorize them as “wicked” or “tame” or into the quadrants of the Cynefin framework. Thus, divergent thinking (brainstorming ideas) will be followed by convergent thinking (filtering out those that aren’t appropriate for their projects).

-

Research design: After their project proposals have been turned in, the students will turn to research design. In a workshop intended to teach the students about research methods, I will have them draw hypotheses and research methods out of a hat and then, on the spot, proposes a research design. Dot-voting or some other mechanism will be used to eliminate unfit designs without any student feeling his term paper plans have been criticized.

-

Argument development: Students are expected to do a thorough literature review and form some expectations (if not hypotheses) about what they expect to find. In the past, they haven’t been very good at identifying opposing arguments and thereby defending against them. I’m working on the design of a workshop called a “straw man check” which would involve the group in brainstorming counter-arguments for each project—hopefully to sharpen their analysis and improve their literature reviews.

-

Writing: Students will proofread and give feedback to one another, thus forcing them to iterate (at least once) on their writing.

-

Overall quality: It will be tricky for me to predict the research quality of the final term papers before they come in. And once I’ve graded them, the students don’t have another chance to iterate. One solution is to have them present their work-in-progress to each other as a “conference” and elicit feedback. The weakness of this is that other students will tend not to be critical, and I doubt the participants learn very much. In order to give them hard, reliable feedback, I’m thinking about a prediction market. What if students could “bet” on which grades their classmates are likely to earn? Then each student could get an honest evaluation of what his classmates think that I will think of his work.

Measuring how well it works

My expectation is that students will learn more about research (and about writing) by treating the design of a research term paper as a wicked problem and iterating with their peers on it, than they would learn without iteration. Moreover, I believe they will develop better quality research in a shorter amount of time; I’m allowing 10 weeks for the term paper in the spring as compared to the full 15 weeks I allowed this fall. Thirdly, I believe the students will feel more satisfied with their own work and less likely to tolerate it as a necessary evil for getting to graduation.

My next task is to iterate on how to measure these outcomes. I’d like to get a baseline of measurement this fall, so I can see what has improved in the spring.